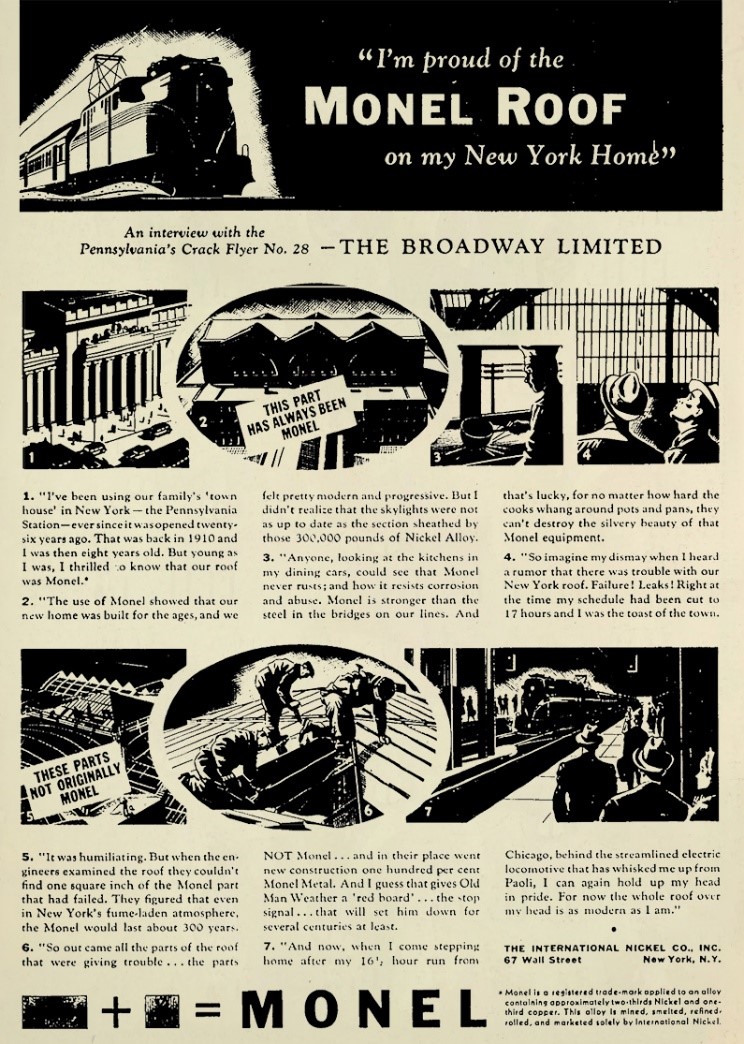

In 2019 I was introduced to a material I had only heard of in passing, Monel®*.

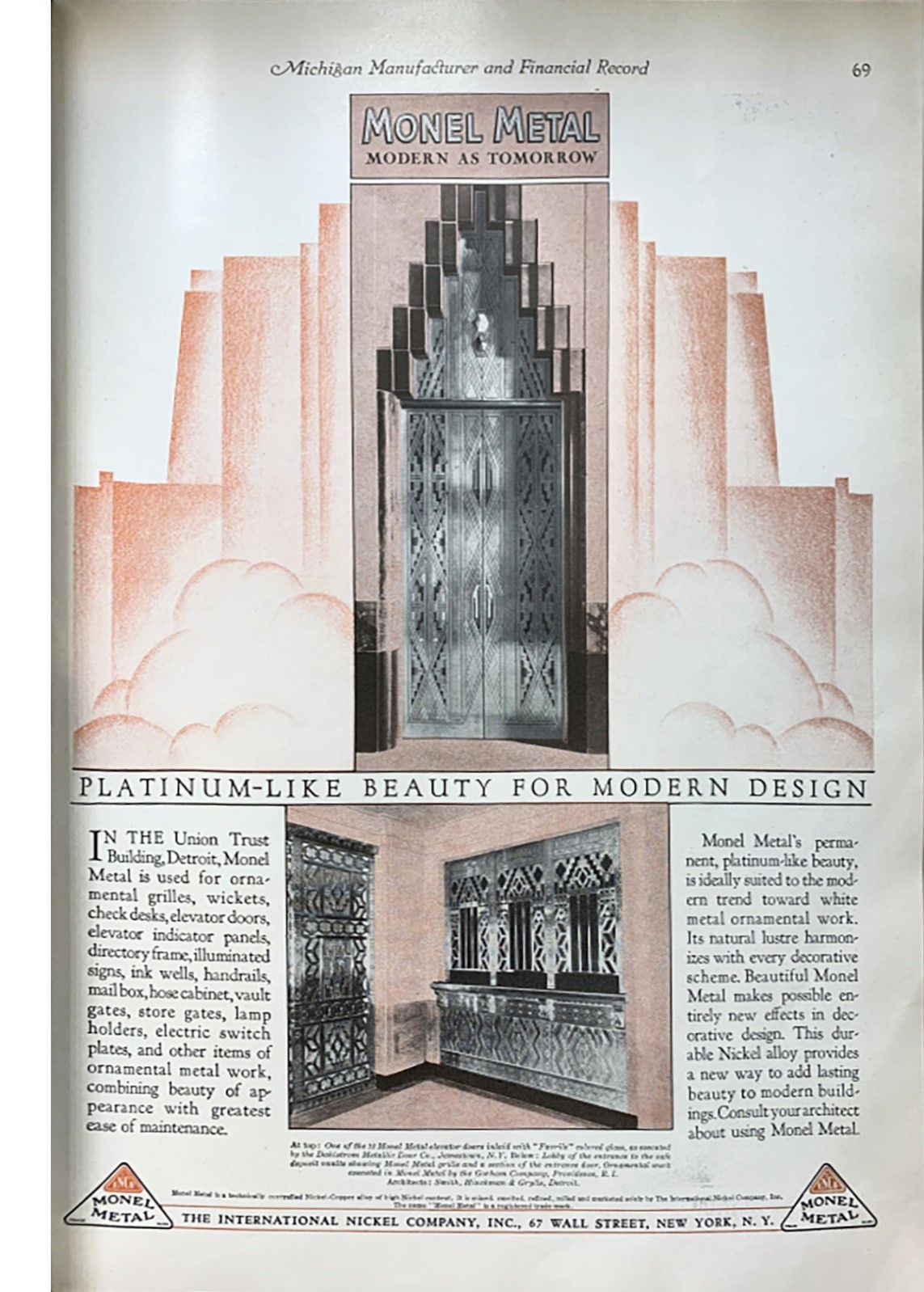

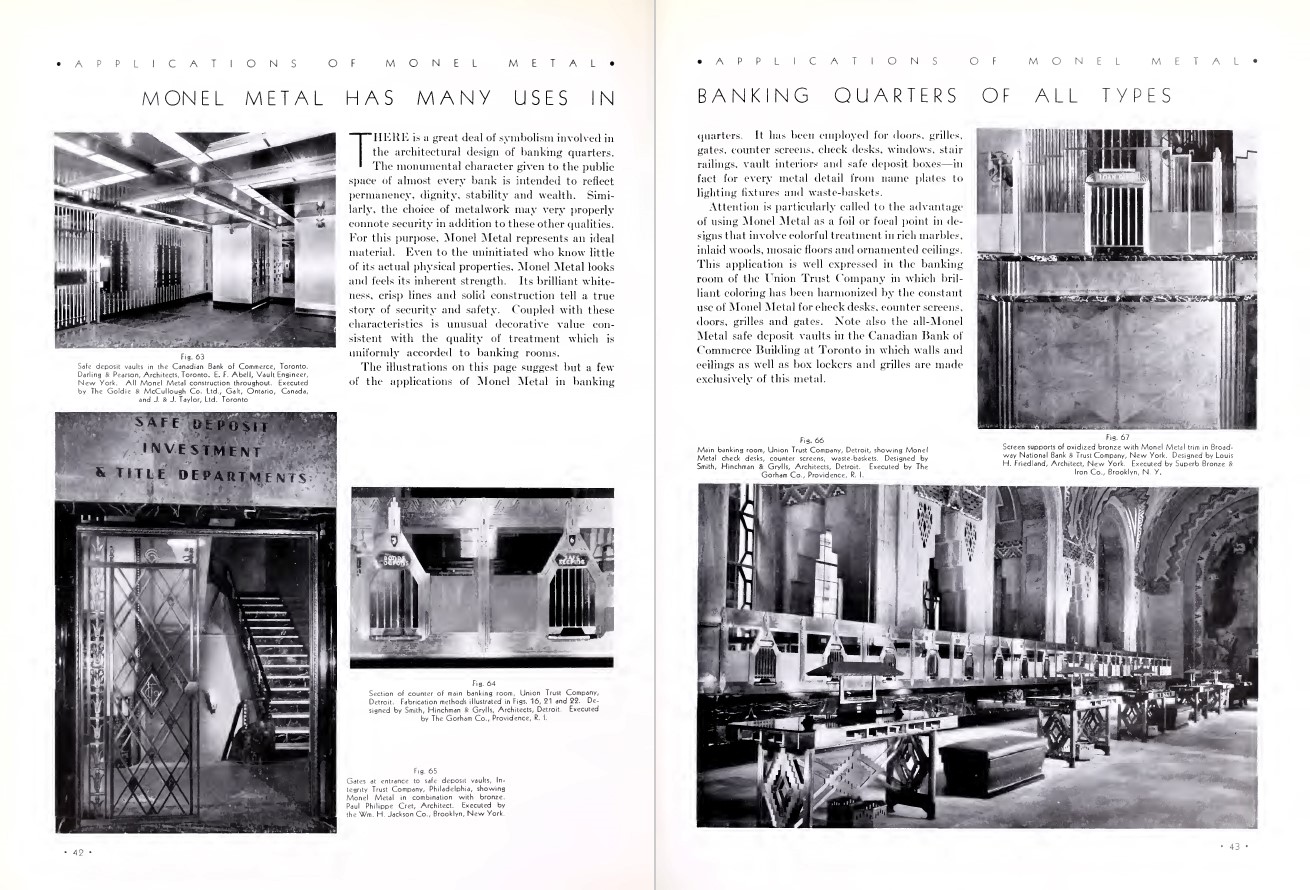

Having previously come across it through the wrought craft of Samuel Yellin, a field trip to the southern tip of Manhattan placed me in front of a gleaming Monel elevator in an art-deco lobby. My interest was piqued. What was this alloy, how was it used and was it still popular?

In an attempt to hunt down interiors, I found redevelopment of department stores and banks, where the metal had flourished, had sadly led to total loss. I also discovered I was not alone in my ignorance. The break-up of the International Nickel Company (INCO) had thrown proprietary research to the wind, while conservators relied on dated marketing material for information. Worse, contractors were dumping Monel significantly before the end of its life cycle.